The day the industry changed

Most people will tell you that the airline industry changed 32 years ago today—the day Jimmy Carter signed the Airline Deregulation Act.

Most people will tell you that the airline industry changed 32 years ago today—the day Jimmy Carter signed the Airline Deregulation Act.

In fact, there are some people who will tell you that October 24, 1978 was the day everything that ever has changed or ever will change in the airline industry, changed.

Not me. For my money, the day the industry changed was 20 years ago, when Young & Rubicam resigned Trans World Airlines.

In 1990, having an airline account was one of the signs that an advertising agency had arrived. It didn’t matter that most of those airlines were on the verge of either bankruptcy or liquidation. Of the ten largest agencies in 1990, four had U.S. airline accounts:

| 1. | Young & Rubicam | Trans World Airlines |

| 2. | Leo Burnett | United Airlines |

| 3. | D’Arcy Masius Benton & Bowles | |

| 4. | Saatchi & Saatchi | Northwest Airlines |

| 5. | J. Walter Thompson | |

| 6. | Foote, Cone & Belding | |

| 7. | Grey | |

| 8. | DDB Needham | |

| 9. | Ogilvy & Mather | Eastern Airlines |

| 10. | McCann-Erickson |

By the same token, most large U.S. airlines employed large advertising agencies:

| American Airlines | Bozell Worldwide, Dallas |

| United Airlines | Leo Burnett, Chicago |

| Delta Air Lines | BBDO, Atlanta |

| Continental Airlines | Wells Rich Greene, New York |

| Eastern Air Lines | Ogilvy & Mather, New York |

| Northwest Airlines | Saatchi & Saatchi, New York |

| Pan American World Airways | Della Femina, McNamee, New York |

| Trans World Airlines | Young & Rubicam, New York |

| USAir | Earl Palmer Brown, Bethesda, MD |

| Southwest Airlines | GSD&M, Austin, TX |

But in 1990, that started to change. The chairman of TWA, corporate raider Carl Icahn, demanded that Young & Rubicam reduce its fee by several million dollars. The agency decided the account wasn’t worth it and resigned. After a review, in which many other agencies declined to participate, a small agency called Avrett Free Ginsberg was awarded the business.

The advertising industry was scandalized; not only was AFG a comparatively tiny agency whose main business was (and still is) pet food, it also reportedly won the business by taking a commission of only 5 percent. At the time, agency commissions were still averaging 10 – 12 percent. Outrage echoed down Madison Avenue.

Twenty years later, here are the top ten U.S. advertising agencies in 2009 according to Advertising Age, along with their airline clients:

| 1. | McCann-Erickson | |

| 2. | BBDO | |

| 3. | JWT | |

| 4. | Young & Rubicam | |

| 5. | Leo Burnett | |

| 6. | DDB | |

| 7. | Saatchi & Saatchi | |

| 8. | DraftFCB | |

| 9. | EuroRSCG | |

| 10. | Grey | Frontier Airlines |

Only one. And it’s a low-cost carrier. Here are ten of the largest U.S. airlines with their advertising agencies. The number in parentheses is the agency’s rank in Advertising Age’s 2010 list of the 800 largest marketing firms in the United States.

| Delta Air Lines | Wieden + Kennedy, New York (61st) |

| American Airlines | TM Advertising, Dallas (184th) |

| United Airlines | Barrie D’Rozario Murphy, Minneapolis (unranked) |

| Continental Airlines | Kaplan Thaler Group, New York (115th) |

| US Airways | Moses Anshell, Phoenix (528th) |

| Southwest Airlines | GSD&M, Austin (115th) |

| JetBlue | Mullen, Boston (87th) |

| Alaska Airlines | WongDoody, Seattle (241st) |

| AirTran | CramerKrasselt, Chicago (41st) |

| Frontier Airlines | Grey, New York (27th) |

Clearly, the days when large airlines employed large agencies are long gone. But what changed?

To answer this question, you need to remember one essential truth: there are only two reasons why an advertising agency will hold on to an account:

- Profits, thereby making agencies and their owners rich.

- Prestige, thereby helping agencies recruit talent, win awards, sign clients, and feel proud of their work.

In the years since Y&R fired TWA, a number of shifts have made airline accounts less attractive—and deregulation played only a small role.

1. Airlines now spend much less on advertising.

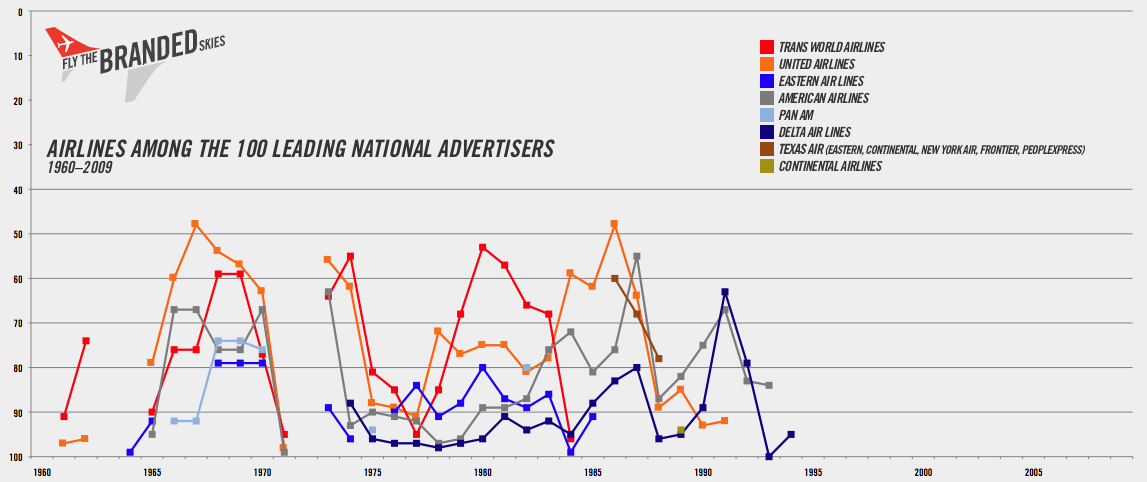

Every year, Advertising Age publishes a list of the top 100 advertisers in the U.S. Here’s how airlines have fared over the past 50 years. You can click on it to expand it.

This graph was compiled after several weekends at the library scanning through microfilms. It is not scientific. For example, at some points during this period the airline holding companies shown owned more than just airlines. In the mid-1980s, UAL, Inc. (the parent company of United Airlines) also owned the Westin and Hilton Hotel chains and Hertz rental cars, which boosted its ranking; when it sold these companies, its ranking among the Leading National Advertisers, previously an artificial 48th, dropped precipitously. Methodology also changed year to year.

But the general trends are very apparent. What this graph shows is the desirability of an airline account relative to other types of account, at least in terms of media outlays.

Airlines have always advertised, but they first started targeting a mass audience when the Jet Age first made air travel available to the masses: TWA and United Airlines broke into the top 100 for the first time in 1961. By the mid-1960s, there were five airlines in the top 100, and in 1967, United—still only an airline—broke into the top 50.

Spending hummed along in the 1970s before deregulation. After deregulation, advertising spending if anything increased relative to other advertisers. In 1982, there were six airlines in the top 100, the highest count ever.

Then, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, two things happened. First, there were fewer airlines. Eastern and Pan Am went out of business. TWA and Continental went into Chapter 11. The airline empire built by Frank Lorenzo disintegrated.

And second, the airlines that remained spent less on advertising. The last airline in the top 100 national advertisers was Delta, at 95, in 1994. Since then?

Nothing.

In 1990, when Young & Rubicam dropped TWA, the airline still spent an estimated $45 million on advertising. In 2009, United Airlines spent $4 million on advertising. To put that in perspective, United spent nearly $6 million in 1961, the first year it was in the top 100.

Leave inflation out of it for a moment. That means United’s spending has dropped 31 percent in the same time Procter & Gamble’s spending has increased nearly 3,700 percent.

In more recent years, Advertising Age has added a list of the top 200 brands to its list of the top 100 advertisers (after all, a single advertiser like Procter & Gamble might have dozens of brands.) In 2009, there was only one airline among the top 200 brands: Southwest Airlines. It spent $190.7 million in measured media. The rest of the industry lagged far behind.

Of course, the size of the media spend isn’t everything. I work at the 11th largest agency in America, according to AdAge, and the brand I work on doesn’t even make it to the top 200 in measured media spending. What matters even more than media spend is profitability.

2. Airline accounts aren’t profitable.

Or at least, they aren’t profitable for large agencies. In 1990, having an airline account was a lot of work. Say a competitor reduced fares. The agency might have to create, produce, and traffic a newspaper ad in just a few days to respond. That’s a considerable amount of work for not much return, at least from the agency’s perspective. Agencies in 1990 made money from producing lavish TV commercials, not from hard-selling retail newspaper ads. And by then, airlines were commissioning fewer and fewer lavish TV commercials.

Smaller agencies generally have lower costs. They have less overhead, they often pay less, and they’re often located in smaller markets than New York (which, you may have heard, is a pretty expensive place to live and work.)

But small agencies not only have lower costs; they’re also willing to work for less. When Y&R lost TWA, it lost an account valued at $45 million. For an agency with well over $2 billion in U.S. billings in 1990, that was peanuts—a little over 2 percent. Imagine if an airline were worth a third, or half, of an agency’s total revenue. It’s no wonder you can push around a small agency on costs in a way you can’t a massive multinational network.

Airline accounts are also not very predictable, and large agencies crave predictability. You can see why in the graph; airlines completely dropped out of the top 100 in 1964 and 1972, and even when they were ranked their spending could be erratic. The airline industry is one of the most sensitive to economic growth, and the marketing budget is one of the most sensitive parts of the airline.

After deregulation, airlines that had kept loose control over their costs were forced to become more disciplined. TWA wasn’t the only airline demanding more from its agency for less. But it took a while for this reality to catch up to the industry. When it did, there was one big reason why.

3. Prestige no longer trumps profits.

There are two factors at play here, and only one of them has anything to do with the airlines.

The first is that the prestige value of an airline account has gone down. Before deregulation, airlines weren’t allowed to compete on price, so they competed on service. This made for some classy advertising, shoots in exotic locales, famous photographers, and celebrity endorsements. An airline account was an account you could be proud to work on. After deregulation, the emphasis of airline advertising shifted to price. Retail ads don’t win awards, and they don’t require expensive shoots. Airline accounts became less prestigious, and more grueling.

Even as the prestige of airline accounts was declining, standards for what constituted a “profitable” account were going up. Starting in the late 1980s, advertising agencies were acquired by large, publicly traded holding companies that have strict requirements for performance. Most of the world’s advertising is now created by agencies owned by one of six multinational holding companies. Under this system, agencies are expected to deliver certain operating margins, and the consequences for falling short of these targets can be dire for agency executives and staff. Advertising agencies today are much less tolerant of money-losing accounts, and even of accounts that make only small profits.

What’s next?

There have been two major airline advertising reviews in the past two years, and they’ve gone in different directions.

In May, JetBlue chose Mullen to replace JWT, going from one of the largest agencies in America to a much smaller one. It’s fair to say JetBlue was a prestige creative account for JWT, and its loss was unfortunate for them. To Mullen, on the other hand, JetBlue was so attractive that the agency gave up its conflicting Orbitz media account to get it—even though Orbitz spends twice as much on advertising. The other finalists in the review (Hill Holliday, Goodby, Tribal DDB, and Grey) were all industry heavyweights.

Last year, a set of even bigger agencies went after Delta Air Lines, including BBDO, Deutsch, Digitas with Saatchi and Saatchi, and Ogilvy & Mather. In the end, Delta Air Lines picked Wieden + Kennedy as its agency of record, replacing the much smaller SS&K. Wieden is a sizable agency; it also has one of the best creative reputations in the industry.

Is it possible airline accounts are back in style?

There are a couple reasons why they might be. First, there have been major shifts in the advertising industry. All clients have become stingier with their marketing dollars, which may mean that airlines don’t look so bad by comparison.

There have also been major shifts in the airline industry. The first is in how people purchase tickets, a revolution that began when Alaska Airlines first started selling airline tickets on its Web site in 1995. By 2008, 50 percent of airline tickets were purchased directly by travelers using airline Web sites or online travel sites such as Expedia. Most of the remainder were purchased using corporate travel agencies.

In all cases, the difference is huge. Individual travelers now see prices from a wide range of airlines on the same screen. Instead of calling one airline to make a reservation, a customer can use Kayak to see prices from all the airlines at once. Price is more important to these consumers than ever, but the fact that the best price can now be found so easily means there is less and less point to advertising fares. Brand advertising is experiencing a resurgence.

The second major shift in the airline industry is the continuing rise of low-cost carriers. As competition among these airlines grows fiercer, brand differentiation becomes more and more important. Airlines like JetBlue, Virgin America, Southwest, and AirTran are all talking about the experience of flying in their ads, and with more personality than the legacy carriers (well, the four that are left.) Ironically, these low-cost carriers are now the prestige accounts of the advertising world.

As with all things, airline accounts are cyclical. We will probably never return to the glory days of airline advertising, but then airline advertising is hardly the only sector in which the advertising industry is undergoing momentous changes. Sadly, TWA is no longer around, but one wonders if today, twenty years later, Young & Rubicam might be willing to take it back.