Why safety isn’t safe

You’re looking at the stupidest airline ad ever produced.

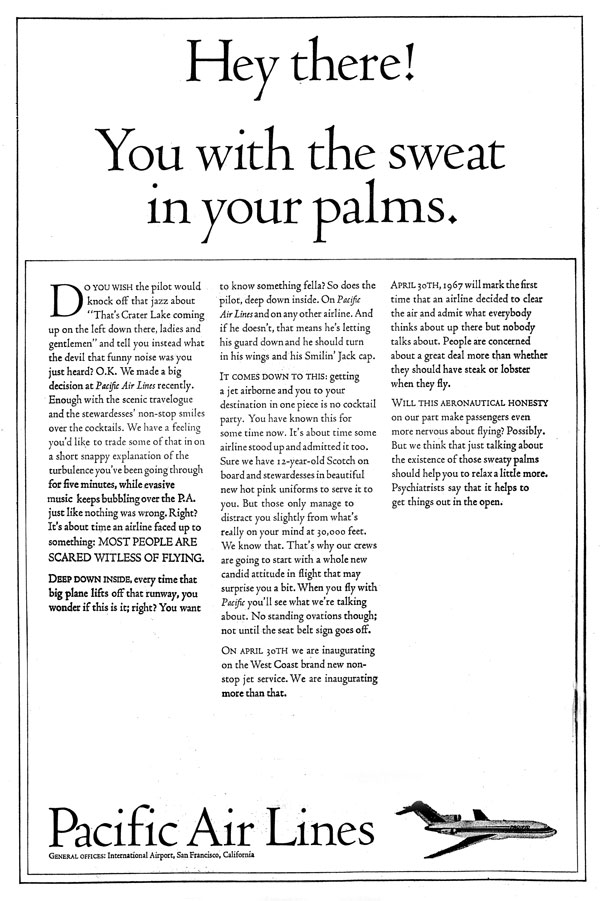

On April 28, 1967, Pacific Air Lines ran this full page ad in the New York Times. It was created by advertising (and comedy) legend Stan Freberg in a bid to bring some honesty to airline advertising. But while the ad may have been honest, it didn’t do much good for Pacific Air Lines.

It is not true, as is often reported, that the ad drove Pacific Air Lines into bankruptcy two months later. In fact, Pacific merged with two other carriers to form Air West, and the forces that compelled the merger had little to do with advertising. But the ad did, within days, cost the jobs of the airline’s vice president of marketing and its director of advertising, and it quickly became notorious.

Passengers don’t like to think about air safety. These days, you’ll almost never see or hear an ad talk about it explicitly. But it was not ever thus.

Today, air travel is extremely safe. But for the first few decades of passenger aviation, it wasn’t. In 1929, the worst year on record, crashes killed 61 people in the United States. Adjusted for the number of people who fly today, that would be like 7,000 people a year dying in plane crashes. In 1929, there was one fatality for every million passenger miles. Now, it’s more like one for every two billion passenger-miles.

Still, that early spotty safety record meant it took some convincing to get Americans to take to the skies. John H. Frederick, a marketing professor from the University of Texas, wrote in 1942 that surveys showed fear was the most important factor preventing people from flying. Cost was a distant second. Frederick counseled the airline industry to pool its resources to inform the public about the development of commercial aviation. In the 1930s and 40s, airlines weren’t shy about touting their safety records: take a look at these ads from the Vintage Ad Browser.

So why don’t airlines often feature safety in their advertising today? Certainly safety is no less important now than it was 60 years ago.

There are a few reasons. The most pragmatic may be that it’s very difficult to substantiate safety claims for airlines. Any airline that wanted to proclaim itself safer than its competitors would have to prove it, and the proof is hard to find. Airlines regularly tout their on-time performance based on FAA statistics. But the FAA doesn’t rank individual airlines based on their safety records. Since accidents are so rare, there would be no way to create any meaningful measurement of an airline’s safety.

There have been efforts to get the FAA to produce a safety report card for individual airlines, both from consumer groups and from the airlines themselves. In 1991, American Airlines CEO Robert Crandall told the Association of National Advertisers that AA was ready to compete on safety:

We think it’s time to put aside the notion that it’s OK for airlines to compete on the thickness of their ham sandwiches and the breadth of their wine selections, but that it’s not nice to talk about the quality of airline maintenance. (Advertising Age, Nov. 4, 1991)

Crandall claimed American had already created storyboards for a commercial to air if the FAA ever started releasing individual statistics. Those storyboards, however, have never been produced, and it’s a good thing. Today, it’s in the interests of airlines to share what they learn from accidents because they all benefit from a safer industry. If safety were to become a point of differentiation between airlines, they might be less forthcoming. Better to stick with the ads about ham sandwiches.

But even if airlines could substantiate safety claims, would they? The Pacific Air Lines case showed that the modern flying public gets a little squeamish when airlines talk about safety.

To me, it’s a little like how I feel when I see the phrase “natural cheese.” It doesn’t make me think the cheese is good. It makes me think of unnatural cheese. Because logically, the cheese maker would only call their cheese “natural” if there was a good reason I might think it wasn’t.

Passengers can be equally suspicious of airlines that talk about safety — and not without cause. After all, an airline would only talk about safety if it had a real or perceived safety problem, right? In the mid-90s, Kiwi International Air Lines, a discount carrier, found it was being lumped in with another discount carrier, ValuJet, which had just suffered a horrific and high-profile crash. Kiwi ran ads boasting of its “perfect safety record.” A few years later, Kiwi was itself shut down by the FAA for safety violations.

After a string of bad crashes in the 1990s, USAir also ran an advertising campaign about new measures it was putting in place to improve its safety record. Unfortunately, I’ve never seen these ads and I can’t find them online. But perhaps a Saturday Night Live parody of the ads will help you imagine what they were like. The parody ended with a jingle: “USAir: We learn something from every crash.”

Here’s the most important answer to the question of why airlines don’t advertise their safety records: They do. This ad, which seems to have run not long after the ValuJet tragedy, is all about safety without ever mentioning it:

This one, from shortly after September 11th, is all about safety too:

Any time you see a commercial featuring a pilot, any time you see a ramp agent marshaling in a plane, any time you hear the words “reliability” or “experience,” or see a plane fly off into the sunset, you are watching a commercial about safety. Airlines know that being explicit is unsettling, so they use code. And that code appears, to some extent, in just about all airline advertising.

Because ultimately, advertising deals in certainties, and airline safety is uncertain. There will always be risks to air travel, no matter how minuscule, and its failures will always be spectacular. To quote Steven Fink, a crisis management expert: “To talk about safety in ads is to play Russian roulette. No matter how safe an airline is or how much is spent on training or maintenance, anything can happen.” (Advertising Age, Dec. 12, 1994)

What do you think? Should airlines compete on safety? Was Stan Freberg simply ahead of his time?